New method uses less computing time for sand

KIT, Disney Research, and Cornell University develop process for efficient computation of photo-realistic images of granular materials, such as sand, snow, salt, or sugar

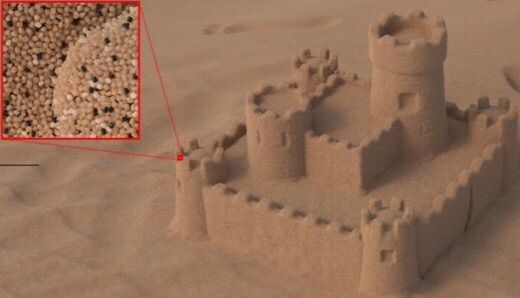

"Objects of granular media, such as a sandcastle, consist of millions or billions of grains. The computation time needed to produce photorealistic images amounts to hundreds to thousands of processor hours," Professor Carsten Dachsbacher of the Institute for Visualization and Data Analysis of KIT explains. Materials, such as sand, salt or sugar, consist of randomly oriented grains that are visible at a closer look only. Image synthesis, the so-called rendering, is very difficult, as the paths of millions of light rays through the grains have to be simulated. "In addition, complex scattering properties of the individual grains and arrangement of the grains in a system can prevent classical acceleration techniques from being used. This makes it difficult to find efficient algorithms," doctoral student Johannes Meng adds. "In case of transparent grains and long light paths, computation time increases disproportionately."

For image synthesis, the researchers developed a new multi-scale process that adapts simulation to the structure of light transport in granular media on various scales. On the finest scale, when only few grains are imaged, geometry, size, and material properties of individual discernable grains as well as their packing density are considered. As in classical approaches, light rays are traced through the virtual grains, which is referred to as path tracing. Path tracing computes light paths from each pixel back to the light sources. This approach, however, cannot be applied to millions or billions of grains.

The new process automatically changes to another rendering technique, i.e. volumetric path tracing, after a few interactions, such as reflections on grains, provided that the contributions of individual interactions can no longer be distinguished. The researchers demonstrated that this method normally applied to the calculation of light scattering in materials, such as clouds or fog, can accurately represent and more efficiently compute light transport in granular materials on these scales.

On larger scales, a diffusion approximation can be applied to produce an analytical and efficient solution for remaining light transport. This enables efficient computation of photorealistic representation in case of bright and strongly reflecting grains, such as snow or sugar.

The researchers also succeeded in demonstrating how the individual techniques have to be combined to produce consistent visual results on all scales - from individual grains to objects made of billions of grains - in images and animations. Depending on the material, the hybrid approach accelerates computation by a factor of ten up to several hundreds compared to conventional path tracing, while image quality remains the same.