Uncovering the cause of sea temperature rise: A hopeless endeavour?

At the bottom of the Bornholm Basin in the central Baltic Sea, the water temperature has risen faster than at the surface in recent decades. In Germany, Warnemünde researchers have now been able to explain this unusual development with a temporal change in the water exchange between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. It ensures that, in addition to the rapid increase in temperature in the surface water, which can be observed everywhere in the Baltic Sea and can be attributed to global warming, the temperature in the deep water also rises. The research results have now been published in the renowned journal Geophysical Research Letters.

We are registering an increase in the surface temperatures of the seas worldwide due to global warming - this is also the case in the Baltic Sea. While the surface water reacts relatively quickly to the higher temperature in the atmosphere, the deeper water absorbs the heat only with a delay. In some areas of the Baltic Sea, however, the lower layers are warming faster than the surface water.

How can that be? Leonie Barghorn, physical oceanographer at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW), together with her colleagues, investigated whether temporal changes in the inflow of North Sea water into the Baltic Sea could be

the cause.

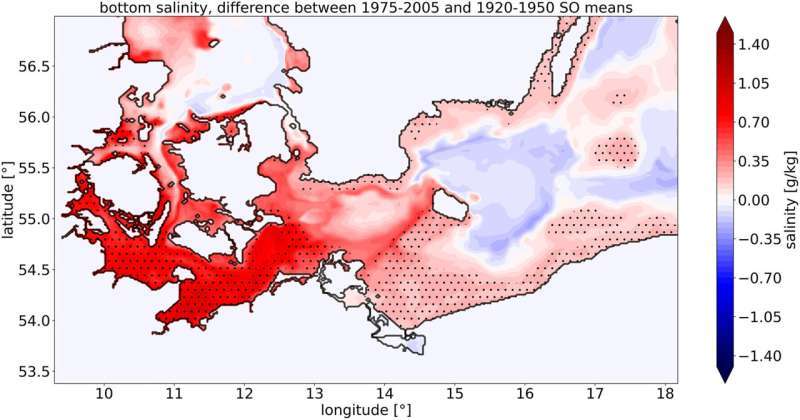

The brackish Baltic Sea gets its salt content from the North Sea. However, due to its higher salt content, the North Sea water flowing in is heavier than the brackish water of the Baltic Sea and therefore flows in at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. This is not a permanent process, because the Baltic Sea usually has a high level due to numerous inflows and large amounts of annual precipitation, which results in a strong outflow. Only under certain meteorological and/or oceanographic conditions do these ratios reverse, so that North Sea water can reach the Baltic Sea.

For decades, the fall and winter storms were thought to be the main drivers of these conditions. In 2002, it was possible for the first time to identify and examine more closely a saltwater inflow that deviated from this pattern: in calm summer weather, an inflow of North Sea water into the Baltic Sea was driven solely by horizontal differences in salinity. While these events are much weaker in scope, they occur more frequently. And of course, North Sea water that flows into the Baltic Sea in summer or early autumn

is significantly warmer than that that enters via winter inflows.

There are still no sufficiently long series of observations on the summer inflows so a trend determination based on the measurement data is too large and is fraught with uncertainty. Leonie Barghorn therefore used the tool of supercomputer simulation to investigate whether the frequency of saltwater inflows in summer and early autumn has increased over the past 150 years and whether there is a causal link to temperature increase in the deep water of the Bornholm Sea. "We analyzed a so-called 'hindcast' simulation, covering the period from 1850 to 2008,” explains Leonie Barghorn of her methodology.

"By comparing the data from the two seasons of summer and early autumn with those of the entire year, it became clear that in the model period under consideration, the summer and early autumn salt input increased and the winter one decreased." While the Arkona Basin upstream of the Bornholm Basin is regularly mixed due to its shallower depth, so that the inflowing warm salt water is distributed over the entire water column, the downstream Gotland Basin is not accessible for the small summer to early autumn saltwater inflows. Thus prevail only in Bornholm Basin Conditions that make this "floor heating" visible.

Co-author Markus Meier adds: "We do not yet know exactly what caused the salt input to be shifted to the warm season. In any case, the consequences for the Bornholm Basin can be serious, because higher temperatures will also drive up oxygen depletion and thus promote the spread of 'dead zones'.”

The research conducted by the Warnemünde team has provided valuable insight into the cause of high temperatures at the bottom of the sea. However, more research is needed to fully understand the underlying mechanisms at play and to develop effective solutions. Without further research, it is unlikely that the cause of these high temperatures can be fully understood or addressed.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?